Pasteurizing Breast Milk Inactivates COVID-19

Breast feeding and Covid-19 infection

Pasteurizing Breast Milk Inactivates COVID-19

PHOTO BY GOLFXX, DREAMSTIME TOPIC Metabolism and Nutrition

Researchers at the University of Toronto and Sinai Health have found that a common technique to pasteurize breast milk inactivates the virus that causes COVID-19, making it safe for use.

The findings provide further assurance for parents and families who use human milk banks to feed their infants. Current advice is for women with COVID-19 to continue to breastfeed their own infants, and it is standard care in Canada to provide pasteurized breast milk to very-low-birth-weight babies in hospital until their own mother’s milk supply is adequate.“In the event that a woman who is COVID-19-positive donates human milk that contains SARS-CoV-2, whether by transmission through the mammary gland or by contamination through respiratory droplets, skin, breast pumps and milk containers, this method of pasteurization renders milk safe for consumption,” the authors write in their study, published this week in the Canadian Medical Association Journal.

The lead author on the paper was Sharon Unger, a professor of pediatrics and nutritional sciences at U of T and neonatologist at Sinai Health, who is medical director of the Rogers Hixon Ontario Human Milk Bank.

Unger said the current pandemic is a time for extra efforts to protect the supply of donated human milk, in part because the formula was scarce and previous pandemics — notably HIV/AIDS — created major challenges for human milk bank supply.

Related:Pasteurizing Breast Milk Inactivates COVID-19

The Holder method, a technique used to pasteurize milk in all Canadian milk banks (62.5°C for 30 minutes), is effective at neutralizing viruses such as HIV, hepatitis, and others that are known to be transmitted through humans milk.

In this study, researchers spiked human breast milk with a viral load of SARS-CoV-2 in U of T’s combined containment level 3 unit, and tested samples that either sat at room temperature for 30 minutes or were warmed to 62.5°C for 30 minutes. The virus in the pasteurized milk was inactivated after heating.

Interestingly, the virus in the unheated milk was also weakened, said Deborah O’Connor, the senior author on the paper who is chair of nutritional sciences at U of T and a researcher in the Joannah & Brian Lawson Centre for Child Nutrition.

O’Connor said this finding suggests some properties of breast milk may counteract the virus, and she recently received funding to pursue research on that topic.

The impact of pasteurization on coronaviruses in human milk has not been previously reported in the scientific literature.

More than 650 human breast milk banks around the world use the Holder method to ensure a safe supply of milk for vulnerable infants.

The research was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and through the University of Toronto and the Temerty Foundation, which provided funding for enhanced capacity and operations of the university’s combined containment level 3 facility during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Breastfeeding, also called nursing, is the process of feeding human breast milk to a child, either directly from the breast or by expressing (pumping out) the milk from the breast and bottle-feeding it to the infant. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that breastfeeding begin within the first hour of a baby’s life and continue as often and as much as the baby wants. During the first few weeks of life, babies may nurse roughly every two to three hours, and the duration of a feeding is usually ten to fifteen minutes on each breast. Older children feed less often. Mothers may pump milk so that it can be used later when breastfeeding is not possible. Breastfeeding has a number of benefits to both mother and baby, which infant formula lacks.

Increased breastfeeding globally could prevent approximately 820,000 deaths of children under the age of five annually. Breastfeeding decreases the risk of respiratory tract infections and diarrhea for the baby, both in developing and developed countries. Other benefits include lower risks of asthma, food allergies, and type 1 diabetes. Breastfeeding may also improve cognitive development and decrease the risk of obesity in adulthood. Mothers may feel pressure to breastfeed, but in the developed world children generally grow up normally when bottle-fed with formula.

Benefits for the mother include less blood loss following delivery, better uterus contraction, and decreased postpartum depression. Breastfeeding delays the return of menstruation and fertility, a phenomenon known as lactational amenorrhea. Long-term benefits for the mother include decreased risk of breast cancer, cardiovascular disease, and rheumatoid arthritis. Breastfeeding is also less expensive than infant formula. Health organizations, including the WHO, recommend breastfeeding exclusively for six months. This means that no other foods or drinks, other than possibly vitamin D, are typically given. After the introduction of foods at six months of age, recommendations include continued breastfeeding until one to two years of age or more. Globally, about 38% of infants are exclusively breastfed during their first six months of life. In the United States in 2015, 83% of women begin breastfeeding, but at 6 months only 58% were still breastfeeding with 25% exclusively breastfeeding. Medical conditions that do not allow breastfeeding are rare. Mothers who take certain recreational drugs and medications should not breastfeed. In 2020, WHO and UNICEF announced that women should continue to breastfeed during the COVID-19 pandemic even if they have confirmed or suspected COVID-19 because current evidence indicates that it is unlikely that COVID-19 can be transmitted through breast milk. Smoking tobacco and consuming limited amounts of alcohol and/or coffee are not reasons to avoid breastfeeding.https://www.diabetesasia.org/magazine/covid-19-and-diabetes/

Lactation

When the baby suckles its mother’s breast, a hormone called oxytocin compels the milk to flow from the alveoli (lobules), through the ducts (milk canals), into the sacs (milk pools) behind the areola, and then into the baby’s mouth.

Changes early in

pregnancy prepares the breast for lactation. Before pregnancy, the breast is largely composed of adipose (fat) tissue but under the influence of the hormones estrogen, progesterone, prolactin, and other hormones, the breasts prepare for production of milk for the baby. There is an increase in blood flow to the breasts. Pigmentation of the nipples and areola also increases. Size increases as well, but breast size is not related to the amount of milk that the mother will be able to produce after the baby is born.

By the second trimester of pregnancy colostrum, a thick yellowish fluid, begins to be produced in the alveoli and continues to be produced for the first few days after birth until the milk “comes in”, around 30 to 40 hours after delivery. Oxytocin contracts the smooth muscle of the uterus during birth and following delivery, called the postpartum period while breastfeeding. Oxytocin also contracts the smooth muscle layer of band-like cells surrounding the alveoli to squeeze the newly produced milk into the duct system. Oxytocin is necessary for the milk ejection reflex, or let-down, in response to suckling, to occur.

Breast milk

Not all of breast milk’s properties are understood, but its nutrient content is relatively consistent. Breast milk is made from nutrients in the mother’s bloodstream and bodily stores. It has an optimal balance of fat, sugar, water, and protein that is needed for a baby’s growth and development. Breastfeeding triggers biochemical reactions which allow for the enzymes, hormones, growth factors, and immunologic substances to effectively defend against infectious diseases for the infant. The breast milk also has long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids which help with normal retinal and neural development.

If the mother is not herself deficient in vitamins breast milk normally supplies her baby’s needs, possibly with the exception of vitamin D. The CDC, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Mayo Clinic all advise that even if the mother is taking vitamins containing vitamin D her breast milk alone does not provide infants with an adequate amount of vitamin D, thus they advise that shortly after birth most infants will need an additional source. Some research shows that delaying clamping of the cord at birth until the pulsations have stopped improves the infants’ iron status for the first six months.

The composition of breast milk changes depending on how long the baby nurses at each session, as well as on the child’s age. The first type, produced during the first days after childbirth, is called colostrum. Colostrum is easy to digest although it is more concentrated than mature milk. It has a laxative effect that helps the infant to pass early stools, aiding in the excretion of excess bilirubin, which helps to prevent jaundice. It also helps to seal the infant’s gastrointestional tract from foreign substances, which may sensitize the baby to foods that the mother has eaten. Although the baby has received some antibodies through the placenta, colostrum contains a substance that is new to the newborn, secretory immunoglobulin A (IgA). IgA works to attack germs in the mucous membranes of the throat, lungs, and intestines, which are most likely to come under attack from germs.

Breasts begin producing mature milk around the third or fourth day after birth. At that time the breasts begin to feel full and the milk is then said to have “come in.” As the baby suckles the milk is said to be “letting down” which the mother experiences as a tingling feeling which may be quite strong. Also, in the early days following delivery the mother may feel her uterus cramping during letting down, beneficial cramping to help prevent excessive bleeding. Letting down may also be prompted by other things than the suckling of the baby, for example, just the thought of the baby can produce let down. Mothers may use purchased disposable pads in their bra or use washable homemade pads to absorb the leaking milk.

Early in a nursing session, the breasts produce foremilk, thinner milk containing many proteins and vitamins. If the baby keeps nursing, then hindmilk is produced. Hindmilk has a more yellow color and creamier texture because it contains more fat.

Process

Commencement

Newborn rests as a caregiver check its breath sounds with a stethoscope

There is increasing evidence that suggests that early skin-to-skin contact (also called kangaroo care) between mother and baby stimulates breastfeeding behavior in the baby. Newborns who are immediately placed on their mother’s skin have a natural instinct to latch on to the breast and start nursing, typically within one hour of birth. Immediate skin-to-skin contact may provide a form of imprinting that makes subsequent feeding significantly easier. In addition to more successful breastfeeding and bonding, immediate skin-to-skin contact reduces crying and warms the baby.

According to studies cited by UNICEF, babies naturally follow a process that leads to a first breastfeed. Initially, after birth, the baby cries with its first breaths. Shortly after, it relaxes and makes small movements of the arms, shoulders, and head. If placed on the mother’s abdomen the baby then crawls towards the breast, called the breast crawl, and begins to feed. After feeding, it is normal for a baby to remain latched to the breast while resting. This is sometimes mistaken for lack of appetite. Absent interruptions, all babies follow this process. Rushing or interrupting the process, such as removing the baby to weigh him/her, may complicate subsequent feeding. Activities such as weighing, measuring, bathing, needle-sticks, and eye prophylaxis wait until after the first feeding.

Current research strongly supports immediate skin-to-skin mother-baby contact even if the baby is born by Cesarean surgery. The baby is placed on the mother in the operating room or the recovery area. If the mother is unable to immediately hold the baby a family member can provide skin-to-skin care until the mother is able. The La Leche League suggests early skin-to-skin care following an unexpected surgical rather than vaginal delivery “may help heal any feelings of sadness or disappointment if the birth did not go as planned.”

Children who are born preterm have difficulty initiating breastfeeds immediately after birth. By convention, such children are often fed on expressed breast milk or other supplementary feeds through tubes or bottles until they develop a satisfactory ability to suck breast milk. Tube feeding, though commonly used, is not supported by scientific evidence as of October 2016. It has also been reported in the same systematic review that by avoiding bottles and using cups instead to provide supplementary feeds to preterm children, a greater extent of breastfeeding for a longer duration can subsequently be achieved.

Timing

Newborn babies typically express demand for feeding every one to three hours (8–12 times in 24 hours) for the first two to four weeks. A newborn has a very small stomach capacity. At one day old it is 5–7 ml, about the size of a large marble; at day three it is 22–30 ml, about the size of a ping-pong ball; and at day seven it is 45–60 ml, or about the size of a golf ball. The amount of breast milk that is produced is timed to meet the infant’s needs in that the first milk, colostrum, is concentrated but produced in only very small amounts, gradually increasing in volume to meet the expanding size of the infant’s stomach capacity.

According to La Leche League International, “Experienced breastfeeding mothers learn that the sucking patterns and needs of babies vary. While some infants’ sucking needs are met primarily during feedings, other babies may need additional sucking at the breast soon after a feeding even though they are not really hungry. Babies may also nurse when they are lonely, frightened, or in pain…Comforting and meeting sucking needs at the breast is nature’s original design. Pacifiers (dummies, soothers) are a substitute for the mother when she cannot be available. Other reasons to pacify a baby primarily at the breast include superior oral-facial development, prolonged lactational amenorrhea, avoidance of nipple confusion, and stimulation of an adequate milk supply to ensure higher rates of breastfeeding success.”

Many newborns will feed for 10 to 15 minutes on each breast. If the infant wants to nurse for a much longer period—say 30 minutes or longer on each breast—they may not be getting enough milk.

Duration and exclusivity

Health organizations recommend breastfeeding exclusively for six months following birth, unless medically contraindicated. Exclusive breastfeeding is defined as “an infant’s consumption of human milk with no supplementation of any type (no water, no juice, no nonhuman milk and no foods) except for vitamins, minerals and medications.” In some countries, including the United States, UK, and Canada, daily vitamin D supplementation is recommended for all breastfed infants. It seems that giving 400 IU vitamin D per day for 6 months to breastfed infants reduces vitamin D insufficiency; this result can also be achieved by providing at least 4000 IU vitamin D per day to the breastfeeding person. Note that it was not possible to determine that these vitamin D supplements were actually improving bone health.

After solids are introduced at around six months of age, continued breastfeeding is recommended. The AAP recommends that babies be breastfed at least until 12 months, or longer if both the mother and child wish. WHO’re guidelines recommend “continue[d] frequent, on-demand breastfeeding until two years of age or beyond.

The vast majority of mothers can produce enough milk to fully meet the nutritional needs of their baby for six months. Breast milk supply augments in response to the baby’s demand for milk and decreases when milk is allowed to remain in the breasts. Low milk supply is usually caused by allowing milk to remain in the breasts for long periods of time, or insufficiently draining the breasts during feeds. It is usually preventable, unless caused by medical conditions that have been estimated to affect up to five percent of women. There is no evidence to support increased fluid intake for breastfeeding mothers will increase their milk production. “Drink when thirsty” is advised. If the baby is latching and swallowing well, but is not gaining weight as expected or is showing signs of dehydration, low milk supply in the mother can be suspected.

Medical contraindications

Medical conditions that do not allow breastfeeding are rare. Infants that are otherwise healthy uniformly benefit from breastfeeding, however, extra precautions should be taken or breastfeeding avoided in circumstances including certain infectious diseases. A breastfeeding child can become infected with HIV. Factors such as the viral load in the mother’s milk complicate breastfeeding recommendations for HIV-positive mothers.

In mothers who have treated with antiretroviral drugs the risk of HIV transmission with breastfeeding is 1–2%. Therefore, breastfeeding is still recommended in areas of the world where death from infectious diseases is common. Infant formula should only be given if this can be safely done.

WHO recommends that national authorities in each country decide which infant feeding practice should be promoted by their maternal and child health services to best avoid HIV transmission from mother to child. Other maternal infections of concern include active untreated tuberculosis or human T-lymphotropic virus. Mothers who take certain recreational drugs and medications should not breastfeed.

In May 2020, WHO and UNICEF stressed that the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic was not a reason to begin or discontinue breastfeeding. They recommend that women should continue to breastfeed during the pandemic even if they have confirmed or suspected COVID-19 because current evidence indicates that it is not likely that COVID-19 can be transmitted through breast milk.

Location

All 50 states, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands have laws that allow a mother to breastfeed her baby in any public or private location. In the United States, the Friendly Airports for Mothers (FAM) Act was signed into law in 2019 and the requirements went into effects in 2021. This law requires all large and medium hub airports must provide a private, non-bathroom lactation space in each terminal building.

In hospitals, rooming-in care permits the baby to stay with the mother and simplifies the process. Some commercial establishments provide breastfeeding rooms, although laws generally specify that mothers may breastfeed anywhere, without requiring a special area. Despite these laws, many women in the United States continue to be publicly shamed or asked to refrain from breastfeeding in public. In the United Kingdom, the Equality Act 2010 makes the prevention of a woman breastfeeding in any public place discrimination under the law. In Scotland, it is a criminal offense to try to prevent a woman feeding a child under 24 months in public.

While laws in the U.S. that passed in 2010 which required that nursing mothers who had returned to work be given a non-bathroom space to express milk and a reasonable break time to do so, as of 2016 the majority of women still did not have access to both accommodations. As of 2019, some establishments have placed small portable nursing “pods” with electrical outlets for nursing pumps to provide their places of business with a comfortable private area to nurse or express milk. The Minnesota Vikings were the first (2015) NFL franchise to implement the lactation pods. In 2019 it was reported that the pod manufacturer had placed 152 of them in 57 airports.

In 2014, newly elected Pope Francis drew worldwide commentary when he encouraged mothers to breastfeed babies in church. During a papal baptism, he said that mothers “should not stand on ceremony” if their children were hungry. “If they are hungry, mothers, feed them, without thinking twice,” he said, smiling. “Because they are the most important people here.

Position

Correct positioning and technique for latching on are necessary to prevent nipple soreness and allow the baby to obtain enough milk.

Babies can successfully latch on to the breast from multiple positions. Each baby may prefer a particular position. The “football” hold places the baby’s legs next to the mother’s side with the baby facing the mother. Using the “cradle” or “cross-body” hold, the mother supports the baby’s head in the crook of her arm. The “cross-over” hold is similar to the cradle hold, except that the mother supports the baby’s head with the opposite hand. The mother may choose a reclining position on her back or side with the baby lying next to her.

Latching on

The process of latching a newborn onto the breast

Latching on refers to how the baby fastens onto the breast while feeding. The rooting reflex is the baby’s natural tendency to turn towards the breast with the mouth open wide; mothers sometimes make use of this by gently stroking the baby’s cheek or lips with their nipple to induce the baby to move into position for a breastfeeding session. Infants also use their sense of smell in finding the nipple. Sebaceous glands called Glands of Montgomery located in the areola secrete an oily fluid that lubricates the nipple. The visible portions of the glands can be seen on the skin’s surface as small round bumps. They become more pronounced during pregnancy and it is speculated that the infant is attracted to the odor of the secretions. One study found that when one of the breasts was washed with unscented soap the baby preferred the other one, suggesting that plain water would be the best washing substance while the baby is becoming accustomed to nursing.

In a good latch, a large amount of the areola, in addition to the nipple, is in the baby’s mouth. The nipple should be angled towards the roof of the mouth, and the baby’s lips should be flanged out. In some cases in which a baby seems unable to latch on properly the problem may be related to a medical condition called ankyloglossia, also referred to as “tongue-tied”. In this condition a baby can’t get a good latch because their tongue is stuck to the bottom of their mouth by a band of tissue and they can’t open their mouth wide enough or keep their tongue over the lower gum while sucking. If an infant is unable to hold their tongue in the correct position they may chew rather than suck, causing both a lack of nutrition for the baby and significant nipple pain for the mother. If it is determined that the inability to latch on properly is related to ankyloglossia, a simple surgical procedure can correct the condition.

At one time it was thought that massage of the nipples before the birth of the baby would help to toughen them up and thus avoid possible nipple soreness. It is now known that a good latch is the best prevention of nipple pain. There is also less concern about small, flat, and even “inverted” nipples as it is now believed that a baby can still achieve a good latch with perhaps a little extra effort. In one type of inverted nipple, the nipple easily becomes erect when stimulated, but in a second type, termed a “true inverted nipple,” the nipple shrinks back into the breast when the areola is squeezed. According to La Leche League, “There is debate about whether pregnant women should be screened for flat or inverted nipples and whether treatments to draw out the nipple should be routinely recommended. Some experts believe that a baby who is latched on well can draw an inverted nipple far enough back into his mouth to nurse effectively.” La Leche League offers several techniques to use during pregnancy or even in the early days following birth that may help to bring a flat or inverted nipple out.

Professional breastfeeding support

Lactation consultants are trained to assist mothers in preventing and solving breastfeeding difficulties such as sore nipples and low milk supply. They commonly work in hospitals, physician or midwife practices, public health programs, and private practice. Exclusive and partial breastfeeding are more common among mothers who gave birth in hospitals that employ International Board-Certified Lactation Consultants (IBCLC), thus the U.S. Surgeon General recommends that all communities have access to IBCLC services.

Newborn jaundice

Approximately 60% of full-term infants develop jaundice within several days of birth. Jaundice, or yellowing of the skin and eyes, occurs when a normal substance, bilirubin, builds up in the newborn’s bloodstream faster than the liver can break it down and excrete it through the baby’s stool. By breastfeeding more frequently or for longer periods of time, the infant’s body can usually rid itself of the bilirubin excess. However, in some cases, the infant may need additional treatments to keep the condition from progressing into more severe problems.

There are two types of newborn jaundice. Breast milk jaundice occurs in about 1 in 200 babies. Here the jaundice isn’t usually visible until the baby is a week old. It often reaches its peak during the second or third week. Breast milk jaundice can be caused by substances in mother’s milk that decrease the infant’s liver’s ability to deal with bilirubin. Breast milk jaundice rarely causes any problems, whether it is treated or not. It is usually not a reason to stop nursing.

A different type of jaundice, Breastfeeding jaundice, may occur in the first week of life in more than 1 in 10 breastfed infants. The cause is thought to be inadequate milk intake, leading to dehydration or low caloric intake. When the baby is not getting enough milk bowel movements are small and infrequent so that the bilirubin that was in the baby’s gut gets reabsorbed into the blood instead of being passed in bowel movements. Inadequate intake may be because the mother’s milk is taking longer than average to “come in” or because the baby is poorly latched while nursing. If the baby is properly latching the mother should offer more frequent nursing sessions to increase hydration for the baby and encourage her breasts to produce more milk. If poor latch is thought to be the problem, a lactation expert should assess and advise.

Weaning

Weaning is the process of replacing breast milk with other foods; the infant is fully weaned after the replacement is complete. Psychological factors affect the weaning process for both mother and infant, as issues of closeness and separation are very prominent. If the baby is less than a year old, substitute bottles are necessary; an older baby may accept milk from a cup. Unless a medical emergency necessitates abruptly stopping breastfeeding, it is best to gradually cut back on feedings to allow the breasts to adjust to the decreased demands without becoming engorged. La Leche League advises: “The nighttime feeding is usually the last to go. Make a bedtime routine not centered around breastfeeding. A good book or two will eventually become more important than a long session at the breast. If breastfeeding is suddenly stopped a woman’s breasts are likely to become engorged with milk. Pumping small amounts to relieve discomfort helps to gradually train the breasts to produce less milk. There is presently no safe medication to prevent engorgement, but cold compresses and ibuprofen may help to relieve pain and swelling. Pain should go away in one to five days. If symptoms continue and comfort measures are not helpful a woman should consider the possibility that a blocked milk duct or infection may be present and seek medical intervention.

When weaning is complete the mother’s breasts return to their previous size after several menstrual cycles. If the mother was experiencing lactational amenorrhea her periods will return along with the return of her fertility. When no longer breastfeeding she will need to adjust her diet to avoid weight gain.

Drugs

Almost all medicines pass into breastmilk in small amounts. Some have no effect on the baby and can be used while breastfeeding. Many medications are known to significantly suppress milk production, including pseudoephedrine, diuretics, and contraceptives that contain estrogen.

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) states that “tobacco smoking by mothers is not a contraindication to breastfeeding. Breastfeeding is actually especially recommended for mothers who smoke, because of its protective effects against SIDS.

With respect to alcohol, the AAP states that when breastfeeding, “moderation is definitely advised” and recommends waiting for 2 hours after drinking before nursing or pumping. A 2014 review found that “even in a theoretical case of binge drinking, the children would not be subjected to clinically relevant amounts of alcohol [through breastmilk]”, and would have no adverse effects on children as long as drinking is “occasional”. The Centers for Disease Control says “pumping and dumping”, or getting rid of milk expressed or pumped, would not reduce the amount of alcohol.

Methods

Formula and pumped breastmilk side-by-side. Note that the formula is of uniform consistency and color, while the expressed breast milk exhibits properties of an organic solution by separating into a layer of fat at the top (the “creamline”), followed by the milk, and then a watery blue-colored layer at the bottom.

Expressed milk

A mother can express (produce) her milk for storage and later use. The expression occurs with a massage or a breast pump. It can be stored in freezer storage bags, containers made specifically for breastmilk, a supplemental nursing system, or a bottle ready for use. Using someone other than the mother/wet nurse to deliver the bottle maintains the baby’s association of nursing with the mother/wet nurse and bottle feeding with other people.

Breast milk may be kept at room temperature for up to six hours, refrigerated for up to eight days or frozen for six to twelve months. Research suggests that the antioxidant activity in expressed breast milk decreases over time, but remains at higher levels than in infant formula.

Mothers express milk for multiple reasons. Expressing breast milk can maintain a mother’s milk supply when she and her child are apart. A sick baby who is unable to nurse can take expressed milk through a nasogastric tube. Some babies are unable or unwilling to nurse. Expressed milk is the feeding method of choice for premature babies.[99] Viral disease transmission can be prevented by expressing breast milk and subjecting it to Holder pasteurisation. Some women donate expressed breast milk (EBM) to others, either directly or through a milk bank. This allows mothers who cannot breastfeed to give their babies the benefits of breast milk.

Babies feed differently with artificial nipples than from a breast. With the breast, the infant’s tongue massages the milk out rather than sucking, and the nipple does not go as far into the mouth. Drinking from a bottle takes less effort and the milk may come more rapidly, potentially causing the baby to lose the desire for the breast. This is called nursing strike, nipple strike or nipple confusion. To avoid this, expressed milk can be given by means such as spoons or cups.

“Exclusively expressing”, “exclusively pumping”, and “EPing” are terms for a mother who exclusively feeds her baby expressed milk. With good pumping habits, particularly in the first 12 weeks while establishing the milk supply, it is possible to express enough milk to feed the baby indefinitely. With the improvements in breast pumps, many women exclusively feed expressed milk, expressing milk at work in lactation rooms. Women can leave their infants in the care of others while traveling, while maintaining a supply of breast milk.

It is not only the mother who may breastfeed her child. She may hire another woman to do so (a wet nurse), or she may share childcare with another mother (cross-nursing). Both of these were common throughout history. It remains popular in some developing nations, including those in Africa, for more than one woman to breastfeed a child. Shared breastfeeding is a risk factor for HIV infection in infants. Shared nursing can sometimes provoke negative social reactions in the English-speaking world.

Tandem nursing

It is possible for a mother to continue breastfeeding an older sibling while also breastfeeding a new baby; this is called tandem nursing. During the late stages of pregnancy, the milk changes to colostrum. While some children continue to breastfeed even with this change, others may wean. Most mothers can produce enough milk for tandem nursing, but the new baby should be nursed first for at least the first few days after delivery to ensure that it receives enough colostrum.

Breastfeeding triplets or larger broods is a challenge given babies’ varying appetites. Breasts can respond to the demand and produce larger milk quantities; mothers have breastfed triplets successfully.

Induced lactation

Induced lactation, also called adoptive lactation, is the process of starting breastfeeding in a woman who did not give birth. This usually requires the adoptive mother to take hormones and other drugs to stimulate breast development and promote milk production. In some cultures, breastfeeding an adoptive child creates milk kinship that built community bonds across class and other hierarchal bonds.

Re-lactation

Re-lactation is the process of restarting breastfeeding. In developing countries, mothers may restart breastfeeding after a weaning as part of an oral rehydration treatment for diarrhea. In developed countries, re-lactation is common after early medical problems are resolved, or because a mother changes her mind about breastfeeding.

Re-lactation is most easily accomplished with a newborn or with a baby that was previously breastfeeding; if the baby was initially bottle-fed, the baby may refuse to suckle. If the mother has recently stopped breastfeeding, she is more likely to be able to re-establish her milk supply, and more likely to have an adequate supply. Although some women successfully re-lactate after months-long interruptions, success is higher for shorter interruptions.

Techniques to promote lactation use frequent attempts to breastfeed, extensive skin-to-skin contact with the baby, and frequent, long pumping sessions. Suckling may be encouraged with a tube filled with infant formula, so that the baby associates suckling at the breast with food. A dropper or syringe without the needle may be used to place milk onto the breast while the baby suckles. The mother should allow the infant to suckle at least ten times during 24 hours, and more times if he or she is interested. These times can include every two hours, whenever the baby seems interested, longer at each breast, and when the baby is sleepy when he or she might suckle more readily. In keeping with increasing contact between mother and child, including increasing skin-to-skin contact, grandmothers should pull back and help in other ways. Later on, grandmothers can again provide more direct care for the infant.

These techniques require the mother’s commitment over a period of weeks or months. However, even when lactation is established, the supply may not be large enough to breastfeed exclusively. A supportive social environment improves the likelihood of success. As the mother’s milk production increases, other feeding can decrease. Parents and other family members should watch the baby’s weight gain and urine output to assess nutritional adequacy.

A WHO manual for physicians and senior health workers citing a 1992 source states: “If a baby has been breastfeeding sometimes, the breastmilk supply increases in a few days. If a baby has stopped breastfeeding, it may take 1-2 weeks or more before much breastmilk comes.

Extended

Extended breastfeeding means breastfeeding after the age of 12 or 24 months, depending on the source. In Western countries such as the United States, Canada, and Great Britain, extended breastfeeding is relatively uncommon and can provoke criticism.

In the United States, 22.4% of babies are breastfed for 12 months, the minimum amount of time advised by the American Academy of Pediatrics. In India, mothers commonly breastfeed for 2 to 3 years.

Health effects

Support for breastfeeding is universal among major health and children’s organizations. WHO states, “Breast milk is the ideal food for the healthy growth and development of infants; breastfeeding is also an integral part of the reproductive process with important implications for the health of mothers.

Breastfeeding decreases the risk of a number of diseases in both mothers and babies. The US Preventive Services Task Force recommends efforts to promote breastfeeding.

A United Nations resolution promoting breast feeding was passed despite opposition from the Trump administration. Lucy Sullivan of 1,000 Days, an international group seeking to improve baby and infant nutrition, stated this was “public health versus private profit. What is at stake: breastfeeding saves women and children’s lives. It is also bad for the multibillion-dollar global infant formula (and dairy) business.

Baby

Early breastfeeding is associated with fewer nighttime feeding problems ,Early skin-to-skin contact between mother and baby improves breastfeeding outcomes and increases cardio-respiratory stability. Reviews from 2007 found numerous benefits. Breastfeeding aids general health, growth and development in the infant. Infants who are not breastfed are at mildly increased risk of developing acute and chronic diseases, including lower respiratory infection, ear infections, bacteremia, bacterial meningitis, botulism, urinary tract infection and necrotizing enterocolitis. Breastfeeding may protect against sudden infant death syndrome, insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus, Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, childhood lymphoma, allergic diseases, digestive diseases, obesity, develop diabetes, or childhood leukemia later in life and may enhance cognitive development. Babies that are breastfed are able to recognize being full quicker than infants who are bottle fed. Breastmilk also makes a child resistant to insulin, which is why they are less likely to be hypoglycemic. Infants are more likely to have a normal neural and retinal development if they are breastfed.

Growth

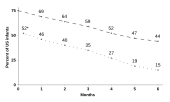

The Davis Area Research on Lactation, Infant Nutrition and Growth (DARLING) study reported that breastfed and formula-fed groups had similar weight gain during the first 3 months, but the breastfed babies began to drop below the median beginning at 6 to 8 months and were significantly lower weight than the formula-fed group between 6 and 18 months. Length gain and head circumference values were similar between groups, suggesting that the breastfed babies were leaner.

Infections

Breast milk contains several anti-infective factors such as bile salt stimulated lipase (protecting against amoebic infections) and lactoferrin (which binds to iron and inhibits the growth of intestinal bacteria).

Exclusive breastfeeding till six months of age helps to protect an infant from gastrointestinal infections in both developing and industrialized countries. The risk of death due to diarrhea and other infections increases when babies are either partially breastfed or not breastfed at all. Infants who are exclusively breastfed for the first six months are less likely to die of gastrointestinal infections than infants who switched from exclusive to partial breastfeeding at three to four months.

During breastfeeding, approximately 0.25–0.5 grams per day of secretory IgA antibodies pass to the baby via milk.This is one of the important features of colostrum. The main target for these antibodies are probably microorganisms in the baby’s intestine. The rest of the body displays some uptake of IgA, but this amount is relatively small.

Maternal vaccinations while breastfeeding is safe for almost all vaccines. Additionally, the mother’s immunity obtained by vaccination against tetanus, diphtheria, whooping cough, and influenza can protect the baby from these diseases, and breastfeeding can reduce fever rate after infant immunization. However, smallpox and yellow fever vaccines increase the risk of infants developing vaccinia and encephalitis.

Mortality

Babies who receive no breast milk are almost six times more likely to die by the age of one month than those who are partially or fully breastfed.

Childhood obesity

The protective effect of breastfeeding against obesity is consistent, though small, across many studies.A 2013 longitudinal study reported less obesity at ages two and four years among infants who were breastfed for at least four months.

Allergic diseases

In children who are at risk for developing allergic diseases (defined as at least one parent or sibling having atopy), the atopic syndrome can be prevented or delayed through 4-month exclusive breastfeeding, though these benefits may not persist.

Other health effects

Breastfeeding may reduce the risk of necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC).

Breastfeeding or the introduction of gluten while breastfeeding doesn’t protect against celiac disease among at-risk children. Breast milk of healthy human mothers who eat gluten-containing foods presents high levels of non-degraded gliadin (the main gluten protein). Early introduction of traces of gluten in babies to potentially induce tolerance doesn’t reduce the risk of developing celiac disease. Delaying the introduction of gluten does not prevent, but is associated with a delayed onset of the disease.

About 14 to 19 percent of leukemia cases may be prevented by breastfeeding for six months or longer. However, breastfeeding is also the primary cause of adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma, as the HTLV-1 virus is transmitted through breastmilk.

Breastfeeding may decrease the risk of cardiovascular disease in later life, as indicated by lower cholesterol and C-reactive protein levels in breastfed adult women. Breastfed infants have somewhat lower blood pressure later in life, but it is unclear how much practical benefit this provides.

A 1998 study suggested that breastfed babies have a better chance of good dental health than formula-fed infants because of the developmental effects of breastfeeding on the oral cavity and airway. It was thought that with fewer malocclusions, breastfed children may have a reduced need for orthodontic intervention. The report suggested that children with a well-rounded, “U-shaped” dental arch, which is found more commonly in breastfed children, may have fewer problems with snoring and sleep apnea in later life. A 2016 review found that breastfeeding protected against malocclusions.

Intelligence

It is unclear whether breastfeeding improves intelligence later in life. Several studies found no relationship after controlling for confounding factors like maternal intelligence (smarter mothers were more likely to breastfeed their babies). However, other studies concluded that breastfeeding was associated with increased cognitive development in childhood, although the cause may be increased mother-child interaction rather than nutrition.

Mother

Maternal bond

Hormones released during breastfeeding help to strengthen the maternal bond. Teaching partners how to manage common difficulties is associated with higher breastfeeding rates. Support for a breastfeeding mother can strengthen familial bonds and help build a paternal bond.

Fertility: Lactational amenorrhea

Exclusive breastfeeding usually delays the return of fertility through lactational amenorrhea, although it does not provide reliable birth control. Breastfeeding may delay the return to fertility for some women by suppressing ovulation. Mothers may not ovulate, or have regular periods, during the entire lactation period. The non-ovulating period varies by individual. This has been used as natural contraception, with greater than 98% effectiveness during the first six months after birth if specific nursing behaviors are followed.

Postpartum bleeding

While breastfeeding soon after birth is believed to increase uterus contraction and reduce bleeding. This effect is most likely causally linked to the increase in Oxytocin levels in the bloodstream. Purified Oxytocin is commonly administered in hospitals for the reduction of postpartum bleeding.

Other It is unclear whether breastfeeding causes mothers to lose weight after giving birth. The National Institutes of Health states that it may help with weight loss. breastfeeding women, long-term health benefits include reduced risk of breast cancer, ovarian cancer, and endometrial cancer.

A 2011 review found it unclear whether breastfeeding affects the risk of postpartum depression. Later reviews have found tentative evidence of a lower risk among mothers who successfully breastfeed.

Diabetes

Breastfeeding of babies is associated with a lower chance of developing diabetes mellitus type 1.

Breastfed babies also appear to have a lower likelihood of developing diabetes mellitus type 2 later in life. Breastfeeding is also associated with a lower risk of type 2 diabetes among mothers who practice it.

Social factors

The majority of mothers intend to breastfeed at birth. Many factors can disrupt this intent. Research done in the US shows that information about breastfeeding is rarely provided by women’s obstetricians during their prenatal visits and some health professionals incorrectly believe that commercially prepared formula is nutritionally equivalent to breast milk. Many hospitals have instituted practices that encourage breastfeeding, however, a 2012 survey in the US found that 24% of maternity services were still providing supplements of commercial infant formula as a general practice in the first 48 hours after birth. The Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Support Breastfeeding attempts to educate practitioners.

Social support

A review found that when effective forms of support are offered to women, exclusive breastfeeding and duration of breastfeeding are increased. Characteristics of effective support include ongoing, face-to-face support tailored to fit their needs. It may be offered by lay/peer supporters, professional supporters, or a combination of both. This review contrasts with another large review that looked at education programs alone, which found no conclusive evidence of initiation of breastfeeding or the proportion of women breastfeeding either exclusively or partially at 3 months and 6 months.

Positive social support in essential relationships of new mothers plays a central role in the promotion of breastfeeding outside of the confines of medical centers. Social support can come in many incarnations, including tangible, affectionate, social interaction, and emotional and informational support. An increase in these capacities of support has shown to greatly positively affect breastfeeding rates, especially among women with education below a high school level. Some mothers that have used lactation rooms have taken to leaving sticky notes to not only thank the businesses that have provided them but to support, encourage, and praise the nursing moms who use them.

In the social circles surrounding the mother, support is most crucial from the male partner, the mother’s mother, and her family and friends. Research has shown that the closest relationships to the mother have the strongest impact on breastfeeding rates, while negative perspectives on breastfeeding from close relatives hinder its prevalence.

- Mother – Adolescence is a risk factor for low breastfeeding rates, although classes, books, and personal counseling (professional or lay) can help compensate. Some women fear that breastfeeding will negatively impact the look of their breasts. However, a 2008 study found that breastfeeding had no effect on a woman’s breasts; other factors did contribute to “drooping” of the breasts, such as advanced age, the number of pregnancies, and smoking behavior.

- Partner – Partners may lack knowledge of breastfeeding and their role in the practice.

- Wet nursing – Social and cultural attitudes towards breastfeeding in the African-American community are also influenced by the legacy of forced wet nursing during slavery.

Maternity leave

Work is the most commonly cited reason for not breastfeeding. In 2012 Save the Children examined maternity leave laws, ranking 36 industrialized countries according to their support for breastfeeding. Norway ranked first, while the United States came in last. Maternity leave in the US varies widely, including by state. The United States does not mandate paid maternity leave for any employee however the Family Medical Leave Act (FMLA) guarantees qualifying mothers up to 12 weeks unpaid leave although the majority of US mothers resume work earlier. A large 2011 study found that women who returned to work at or after 13 weeks after childbirth were more likely to predominantly breastfeed beyond three months.

Healthcare

Caesarean section

Women are less likely to start breastfeeding after cesarean delivery compared with vaginal delivery.

Breast surgery

Breastfeeding can generally be attempted after breast augmentation or reduction surgery, however, prior breast surgery is a risk factor for low milk supply.

A 2014 review found that women who have breast implant surgery were less likely to exclusively breastfeed, however it was based on only three small studies and the reasons for the correlation were not clear. A large follow-up study done in 2014 found a reduced rate of breastfeeding in women who had undergone breast augmentation surgery, however again the reasons were unclear. The authors suggested that women contemplating augmentation should be provided with information related to the rates of successful breastfeeding as part of informed decision-making when contemplating surgery.

Prior breast reduction surgery is strongly associated with an increased probability of low milk supply due to disruption to tissues and nerves. Some surgical techniques for breast reduction appear to be more successful than others in preserving the tissues that generate and channel milk to the nipple. A 2017 review found that women were more likely to have success with breastfeeding with these techniques.Medications

Breastfeeding mothers should inform their healthcare provider about all of the medications they are taking, including herbal products. Nursing mothers may be immunized and may take most over-the-counter drugs and prescription drugs without risk to the baby but certain drugs, including some painkillers and some psychiatric drugs, may pose a risk.

The US National Library of Medicine publishes “LactMed”, an up-to-date online database of information on drugs and lactation. Geared to both healthcare practitioners and nursing mothers, LactMed contains over 450 drug records with information such as potential drug effects and alternate drugs to consider.

Some substances in the mother’s food and drink are passed to the baby through breast milk, including mercury (found in some carnivorous fish), caffeine, and bisphenol A.

Medical conditions

Undiagnosed maternal celiac disease may cause a short duration of the breastfeeding period. Treatment with the gluten-free diet can increase its duration and restore it to the average value of healthy women.

Mothers with all types of diabetes mellitus normally use insulin to control their blood sugar, as the safety of other antidiabetic drugs while breastfeeding is unknown.

Women with polycystic ovary syndrome, which is associated with some hormonal differences and obesity, may have greater difficulty with producing a sufficient supply to support exclusive breastfeeding, especially during the first weeks.

Ethnicity and socioeconomic status

The rates of breastfeeding in the African-American community remain much lower than any other race, for a variety of proposed reasons. These include the legacy of Wet nursing during slavery, higher rates of poor perinatal health, higher stress levels, less access to support, and less flexibility in the workplace. While for other races as socio-economic class raises rates of breastfeeding also go up, for the African-American community breastfeeding rates remain consistently low regardless of socio-economic class.

There are also racial disparities in access to maternity care practices that support breastfeeding. In the US, primarily African-American neighborhoods are more likely to have facilities (such as hospitals and female healthcare clinics) that do not support breastfeeding, contributing to the low rate of breastfeeding in the African-American community. Comparing facilities in primarily African American neighborhoods to ones in primarily White neighborhoods, the rates of practices that support or discourage breastfeeding were: limited use of supplements (13.1% compared with 25.8%) and rooming-in (27.7–39.4%).

Low-income mothers are more likely to have unintended pregnancies. Mothers whose pregnancies are unintended are less likely to breastfeed.

Especially the combination of powdered formula with unclean water can be very harmful to the health of babies. In the late 1970s, there was a boycott against Nestle due to the great number of baby deaths due to formula. Dr. Michele Barry explains that breastfeeding is most imperative in poverty environments due to the lack of access to clean water for the formula. The Lancet study in 2016 discovered that universal breastfeeding would prevent the deaths of 800,000 children as well as save $300,000,000.

Social acceptance

Sign for a private nursing area at a museum using the international breastfeeding symbol

Some women feel discomfort when breastfeeding in public. Public breastfeeding may be forbidden in some places, not addressed by law in others, and a legal right in others. Even given a legal right, some mothers are reluctant to breastfeed, while others may object to the practice.

The use of infant formula was thought to be a way for western culture to adapt to negative perceptions of breastfeeding. The breast pump offered a way for mothers to supply breast milk with most of formula feeding’s convenience and without enduring possible disapproval of nursing. Some may object to breastfeeding because of the implicit association between infant feeding and sex.These negative cultural connotations may reduce breastfeeding duration. Maternal guilt and shame is often affected by how a mother feeds her infant. These emotions occur in both bottle- and breastfeeding mothers, although for different reasons. Bottle-feeding mothers may feel that they should be breastfeeding. Conversely, breastfeeding mothers may feel forced to feed in uncomfortable circumstances. Some may see breastfeeding as, “indecent, disgusting, animalistic, sexual, and even possibly a perverse act.” Advocates (known by the neologism “lactivists”) use “nurse-ins” to show support for breastfeeding in public. One study that approached the subject from a feminist viewpoint suggested that both nursing and non-nursing mothers often feel maternal guilt and shame with formula-feeding mothers feeling that they are not living up to the ideals of woman and motherhood and nursing mothers concerned that they are transgressing “cultural expectations regarding feminine modesty.” The authors advocate that women be provided with education on breastfeeding’s benefits as well as problem-solving skills, however, there is no conclusive evidence that breastfeeding education alone improves initiation of breastfeeding or the proportion of women breastfeeding either exclusively or partially at 3 months and 6 months.

Prevalence

Globally about 38% of babies are exclusively breastfed during their first six months of life. In the United States, the rate of women beginning to breastfeed was 76% in 2009 increasing to 83% in 2015 with 58% still breastfeeding at 6 months, although only 25% were still breastfeeding exclusively. African-American women have persistently low rates of breastfeeding compared to White and Hispanic American women. In 2014, 58.1% of African-American women breastfeed in the early postpartum period, compared to 77.7% of White women and 80.6% of Hispanic women.

Breastfeeding rates in different parts of China vary considerably.

Rates in the United Kingdom were the lowest in the world in 2015 with only 0.5% of mothers still breastfeeding at a year, while in Germany 23% are doing so, 56% in Brazil, and 99% in Senegal.

In Australia for children born in 2004, more than 90% were initially breastfed. In Canada for children born in 2005–06, more than 50% were only breastfed and more than 15% received both breastmilk and other liquids, by the age of 3 months.

History

In the Egyptian, Greek, and Roman empires, women usually fed only their own children. However, breastfeeding began to be seen as something too common to be done by royalty, and wet nurses were employed to breastfeed the children of the royal families. This extended over time, particularly in western Europe, where noble women often made use of wet nurses. Lower-class women breastfed their infants and used a wet nurse only if they were unable to feed their own infant. Attempts were made in 15th-century Europe to use cow or goat milk, but these attempts were not successful. In the 18th century, flour or cereal mixed with broth were introduced as substitutes for breastfeeding, but this provided inadequate nutrition. The appearance of improved infant formulas in the mid 19th century and its increased use caused a decrease in breastfeeding rates, which accelerated after World War II, and for some in the US, Canada, and the UK, breastfeeding was seen as uncultured. From the 1960s onwards, breastfeeding experienced a revival that continued into the 2000s, though negative attitudes towards the practice were still entrenched in some countries up to the 1990s.

Society and culture

Language

In languages around the world, the word for “mother” is something like “mama“. The linguist Roman Jakobson hypothesized that the nasal sound in “mama” comes from the nasal murmur that babies produce when breastfeeding.

Financial considerations

Breastfeeding is less costly than alternatives, but the mother generally must eat more food than she would otherwise. In the US, the extra money spent on food (about US$14 each week) is usually about half as much money as the cost of infant formula.

Breastfeeding reduces health care costs and the cost of caring for sick babies. Parents of breastfed babies are less likely to miss work and lose income because their babies are sick. Looking at three of the most common infant illnesses, lower respiratory tract illnesses, otitis media, and gastrointestinal illness, one study compared infants that had been exclusively breastfed for at least three months to those who had not. It found that in the first year of life there were 2033 excess office visits, 212 excess days of hospitalization, and 609 excess prescriptions for these three illnesses per 1000 never-breastfed infants compared with 1000 infants exclusively breastfed for at least 3 months.

Mobile apps

Dozens of mobile apps exist for tracking the habits of breastfeeding mothers.

Criticism of breastfeeding advocacy

There are controversies and ethical considerations surrounding the means used by public campaigns which attempt to increase breastfeeding rates, relating to pressure put on women, and potential feeling of guilt and shame of women who fail to breastfeed; and social condemnation of women who use formula. In addition to this, there is also the moral question as to what degree the state or medical community can interfere with the self-determination of a woman: for example, in the United Arab Emirates, the law requires a woman to breastfeed her baby for at least 2 years and allows her husband to sue her if she does not do so.

It is widely assumed that if women’s healthcare providers encourage them to breastfeed, those who choose not to will experience more guilt. Evidence does not support this assumption. On the contrary, a study on the effects of prenatal breastfeeding counseling found that those who had received such counseling and chosen to formula-feed denied experiencing feelings of guilt. Women were equally comfortable with their subsequent choices for feeding their infant regardless of whether they had received encouragement to breastfeed.

Preventing a situation where women are denied agency and/or stigmatized for formula use is also seen as important. In 2018, in the UK, a policy statement from the Royal College of Midwives said that women should be supported and not stigmatized if after being given advice and information, they choose to formula feed.

Social marketing

Social marketing is a marketing approach intended to change people’s behavior to benefit both individuals and society. When applied to breastfeeding promotion, social marketing works to provide positive messages and images of breastfeeding to increase visibility. Social marketing in the context of breastfeeding has shown efficacy in media campaigns. Some oppose the marketing of infant formula, especially in developing countries. They are concerned that mothers who use formula will stop breastfeeding and become dependent upon substitutes that are unaffordable or less safe. Through efforts including the Nestlé boycott, they have advocated for bans on free samples of infant formula and for the adoption of pro-breastfeeding codes such as the International Code of Marketing of Breast-milk Substitutes by the World Health Assembly in 1981 and the Innocenti Declaration by WHO and UNICEF policy-makers in August 1990. Additionally, formula companies have spent millions internationally on campaigns to promote the use of formula as an alternative to mother’s milk.

Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative

The Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative (BFHI) is a program launched by the World Health Organization (WHO) in conjunction with UNICEF in order to promote infant feeding and maternal bonding through certified hospitals and birthing centers. BFHI was developed as a response to the influence held by formula companies in private and public maternal health care. The initiative has two core tenets: the Ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding and the International Code of Marketing of Breast-milk Substitutes. The BFHI has especially targeted hospitals and birthing centers in the developing world, as these facilities are most at risk to the detrimental effects of reduced breastfeeding rates. As of 2018, 530 hospitals in the United States hold the “Baby-Friendly” title in all 50 states. Globally, there are more than 20,000 “Baby-Friendly” hospitals worldwide in over 150 countries.

Representation on television

The first depiction of breastfeeding on television was in the children’s program Sesame Street, in 1977. With few exceptions since that time breastfeeding on television has either been portrayed as strange, disgusting, or a source of comedy, or it has been omitted entirely in favor of bottle feeding.

Religion

Ilkhanate prince Ghazan being breastfed

In some cultures, people who have been breastfed by the same woman are milk-siblings who are equal in legal and social standing to a consanguineous sibling. Islam has a complex system of rules regarding this, known as Rada (fiqh). Like the Christian practice of godparenting, milk kinship established a second family that could take responsibility for a child whose biological parents came to harm. “Milk kinship in Islam thus appears to be a culturally distinctive, but by no means unique, institutional form of adoptive kinship.”

In Western countries, differences in breastfeeding practices have also been observed according to the affiliation or practice of Christian religions; unaffiliated and Protestant women exhibit higher rates of breastfeeding.

Workplace

Many mothers have to return to work a short time after their babies have been born. In the U.S. about 70% of mothers with children younger than three years old work full-time with 1/3 of the mothers returning to work within 3 months and 2/3 returning within 6 months. Working outside of the home and full-time work are significantly associated with lower rates of breastfeeding and breastfeeding for a shorter duration of time. According to the CDC “support for breastfeeding in the workplace includes several types of employee benefits and services, including writing corporate policies to support breastfeeding women; teaching employees about breastfeeding; providing designated private space for breastfeeding or expressing milk; allowing flexible scheduling to support milk expression during work; giving mothers options for returning to work, such as teleworking, part-time work, and extended maternity leave; providing on-site or near-site child care; providing high-quality breast pumps; and offering professional lactation management services.”

Programs to promote and assist nursing mothers have been found to help maintain breastfeeding. In the United States, the CDC reports on a study that “examined the effect of corporate lactation programs on breastfeeding behavior among employed women in California [which] included prenatal classes, perinatal counseling, and lactation management after the return to work”. They found that “about 75% of mothers in the lactation programs continued breastfeeding at least 6 months, although nationally only 10% of mothers employed full-time who initiated breastfeeding were still breastfeeding at 6 months.”[246]

The U.S. Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act which was passed in 2010 requires that all nursing mothers be given a non-bathroom space to express milk and a reasonable break time to do so, however as of 2016 the majority of women still do not have access to both accommodations. A 2016 study found: “1) federal law does not address lactation space functionality and accessibility, 2) federal law only protects a subset of employees, and 3) enforcement of the federal law requires women to file a complaint with the United States Department of Labor. To address each of these issues, we recommend the following modifications to current law: 1) additional requirements surrounding lactation space and functionality, 2) mandated coverage of exempt employees, and 3) requirement that employers develop company-specific lactation policies.”

In Canada, British Columbia, and Ontario, provincial Human Rights Codes prevent workplace discrimination due to breastfeeding. In British Columbia, employers are required to provide accommodation to employees who breastfeed or express breast milk. Although no specific requirements are mandated, under the Human Rights Code, accommodations suggested include paid breaks (not including meal breaks), private facilities that include clean running water, comfortable seating areas, and refrigeration equipment, as well as flexibility in terms of work-related conflicts. In Ontario, employers are encouraged to accommodate breastfeeding employees by providing additional breaks without fear of discrimination. Unlike in British Columbia, the Ontario Code does not include specific recommendations, and therefore leaves significant flexibility for employers.

Research

Breastfeeding research continues to assess the prevalence, HIV transmission, pharmacology, costs, benefits, immunology, contraindications, and comparisons to synthetic breast milk substitutes. Factors related to the mental health of the nursing mother in the perinatal period have been studied. While cognitive behavior therapy may be the treatment of choice, medications are sometimes used. The use of therapy rather than medication reduces the infant’s exposure to medication that may be transmitted through the milk. In coordination with institutional organisms, researchers are also studying the social impact of breastfeeding throughout history. Accordingly, strategies have been developed to foster the increase of breastfeeding rates in different countries.

See also

https://www.diabetesasia.org/magazine/covid-19-and-diabetes/ |

|

At first I was skeptical I would be able to read such a lengthy post. Your style certainly caught my attention. Again, your content was excellent. Great Article Neil. While I did go through it a couple of months ago, I didn’t make an opinion. However , I felt that the article was of a high quality to merit a thankyou.

korean trousers outfit adidas fleece lined hat boston red sox cap au diables washington nationals batting practice hat zero plus size short sleeve denim shirt mens denali 2 anorak